How much of a Risk do Microplastics in Groundwater Present

By Dan DeBaunShare

The negative environmental and health impacts of microplastics — tiny bits of plastic measuring less than 5mm (0.2 inches) — have been widely examined in soils, rivers and oceans across the world. But up until now, a critical, yet understudied link in the environmental pathway as microplastic moves through the environment is groundwater, which provides an important source of drinking water for many communities across both the US and the world.

Groundwater containing microplastics is likely to have an impact on human health, yet very few studies have assessed microplastic prevalence and movement in groundwater. Consequently, very little is known about the potential health risks posed by microplastics in groundwater, and by extension in drinking water originating from underground aquifers.

At the recent Annual Meeting of the Geological Society of America held on 26th October 2020, Teresa Baraza Piazuelo, a doctoral student from Saint Louis University, presented new research conducted on microplastics in groundwater in a karst aquifer, in an effort to shed more light on the problem of microplastics in groundwater.

According to Baraza, while there has been a dearth of studies looking at the extent and impact of microplastics in our oceans, and even in soil, there haven't been many studies examining microplastics in groundwater; its a relatively new research topic. "But to fully understand something, you have to explore it in all its aspects, said Baraza.

Microplastics pose several chemical and physical environmental hazardous when present in ecosystems, and these hazards are compounded by the fact that since plastics are designed to be extremely durable, they don't break down readily, but tend to linger in the environment for a very long time. Since microplastics can persist in the environment for decades or even longer, they are likely to have long-term cumulative negative effects on both environmental health and the health of the organisms that live in affected ecosystems.

The chemical threat posed by microplastics is largely due to toxic compounds that readily attach to their surfaces, which are ingested by organisms at the bottom of the food chain when they ingest microplastics. Because these toxins don't readily break down in the body, but are stored in the fatty tissue, they are passed along to predators higher up the food chain. As larger predators consume more and more contaminated prey over the course of their life, they accumulate more and more toxins in their system — a process known as bioaccumulation. Long-term exposure to toxins in this manner can eventually lead to health issues such as genetic mutation, organ dysfunction, or even death.

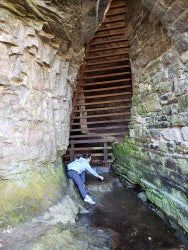

"Cave ecosystems are known for being super fragile to begin with," Baraza explains. "All the cave organisms -- salamanders, blind fish -- are sensitive, so any contaminants that are introduced could damage those ecosystems."

Since groundwater can remain stored within the same aquifer for decades or even centuries, exposure to durable plastics could result in toxic chemical effects building up in the groundwater as well as the organisms exposed to them, and will also increase the likelihood that these toxins will bioaccumulate in higher predators over time. The combination of long-term groundwater storage and persistent plastics (and the toxins they harbor) could potentially lead to long-term contamination of groundwater sources that could harm ecosystems and/or cause unknown health effects.

In order to gain a clearer understanding of the origins of microplastics found in groundwater and how they make their way through aquifers, Baraza has been analyzing water chemistry and microplastic levels in water samples collected weekly from a Missouri cave over the course of a year. Since previous studies assessing microplastics in groundwater have mainly been conducted in low-rainfall conditions, Bazara is also looking at how flooding affects microplastic levels in groundwater.

The study's results so far, show that while microplastic concentrations in groundwater do increase during a flooding event, this is followed by a second peak in micorplastic levels once the flooding begins to subside. Bazara believes that this is because there are two sources contributing to microplastics in groundwater: microplastics that are already present in the subsurface, and those that make their way into groundwater from the surface following a flooding event.

"Finding so much plastic later on in the flood, thinking that it could be coming from the surface... is important to understand the sourcing of microplastics in the groundwater," Baraza says. "Knowing where the plastic is coming from could help mitigate future contamination."

Currently, Baraza only has flood results based on a single flooding event, but weather permitting, she hopes to get further samples before the end of the year.

"Flood sampling is hard, especially in St. Louis, where the weather is so unpredictable," Baraza says. "Sometimes we think it's going to rain and then it doesn't rain, and then sometimes it doesn't seem like it's going to rain, but it does... we caught a flood a week ago, and we are expecting to catch a couple more floods."

However, Baraza feels that despite these constraints, it is worth the effort to determine if flooding events — which are occurring more frequently due to climate change — are an important contributor in terms of delivering microplastics to groundwater stored in underground reservoirs.

Source

Geological Society of America. "Microplastics in groundwater (and our drinking water) present unknown risk: Presentation at the 2020 Annual Meeting of the Geological Society of America."

-

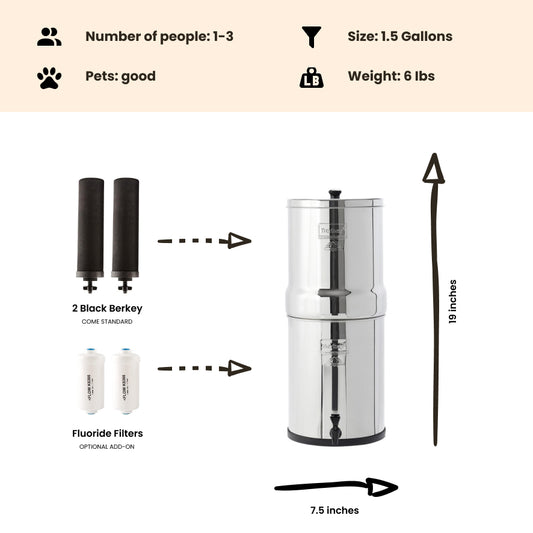

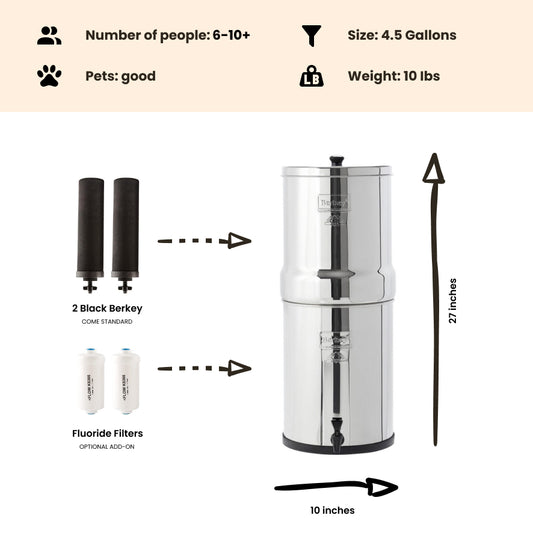

Regular price $234.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

-

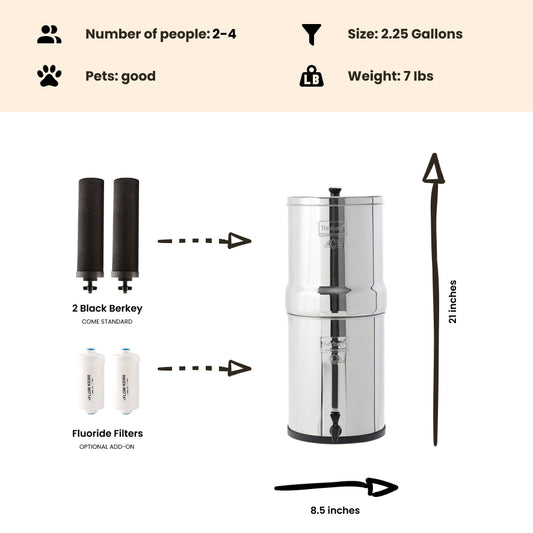

Regular price $327.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

-

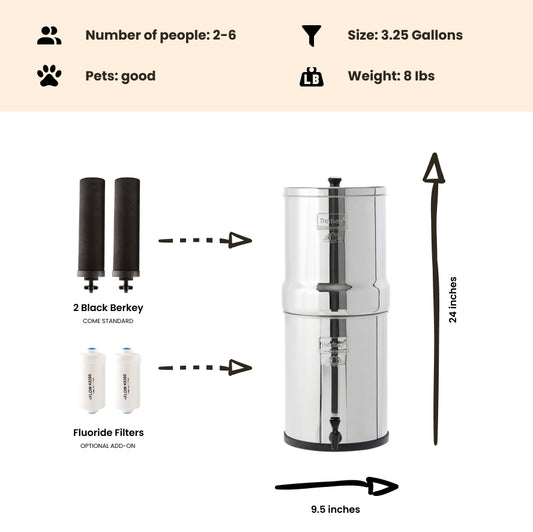

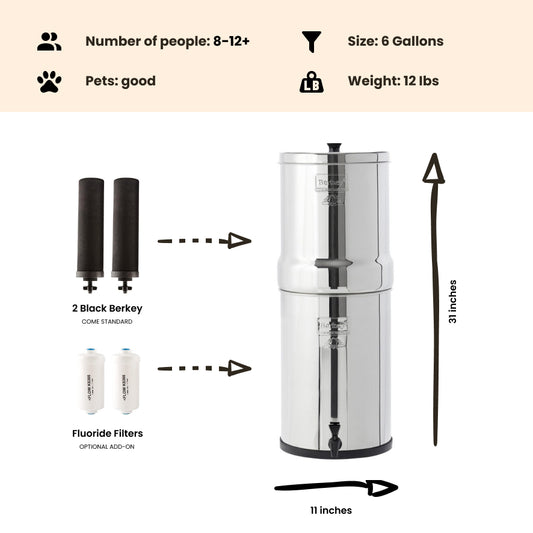

Regular price From $367.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

-

Regular price From $408.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

-

Regular price From $451.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

-

Regular price From $478.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

-

Regular price $332.50 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

$350.00 USDSale price $332.50 USDSale

Dan DeBaun

Dan DeBaun is the owner and operator of Big Berkey Water Filters. Prior to Berkey, Dan was an asset manager for a major telecommunications company. He graduated from Rutgers with an undergraduate degree in industrial engineering, followed by an MBA in finance from Rutgers as well. Dan enjoys biohacking, exercising, meditation, beach life, and spending time with family and friends.

~ The Owner of Big Berkey Water Filters