Study Reveals Elevated Mercury Levels in Groundwater due to Wastewater Disposal

By Dan DeBaunShare

As Cape Cod towns wrestle with problems associated with septic systems, a study that was recently published in the scientific journal Environmental Science and Technology (Nov 2013) shows that treated wastewater disposed in-ground can result in higher levels of mercury in groundwater.

The study, conducted by Carl Lamborg, a biogeochemist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), shows that when wastewater is broken down by microbes, mercury is transformed into a more toxic and more mobile form.

Mercury (Hg) is a highly toxic metal that is present in trace amounts in wastewater; however, Lamborg discovered that the mercury concentrations in both the soil and the water increase as a result of chemical processes that take place during as the waste is decomposed.

Lamborg monitored mercury concentrations and forms over a two year period between 2010-1012 at U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) sampling wells set up around a wastewater treatment site in Cape Cod that disposed wastewater into the ground over a 60 year period between 1936-1995. This wastewater disposal resulted in a contamination plume that stretches nearly two miles downstream from the disposal site, and which travels through the underground aquifer at a rate of approximately 650 feet a year, ending up in a saltwater pond on the coast.

According to Lamborg, who conducted the chemical analysis of the water samples at his WHOI laboratory: “The amount of mercury flowing out of the watershed and into the ocean and these ponds is something like twice as much as it would be if wastewater was not being put into the ground.”

To get a clearer picture of why this was happening Lamborg focused on two sites situated within the contaminant plume where carbon and nitrogen within the waste had been broken down by microbes, who had used up all the available oxygen in the groundwater and sediments in the process, resulting in anoxic conditions at these sites.

At the first sample site, which was closer to the point of wastewater disposal, Lamborg found that microbes were utilizing iron in the breakdown process – a process referred to as iron reduction – and that the more commonly found form of mercury (Hg2+), which is less mobile, was transformed into a more mobile form of elemental mercury (Hg0) that leaches into the groundwater more readily and gets transported further downstream.

At the second site, which was situated further downstream, Lamborg found higher concentrations of yet another form of mercury, monomethylmercury (MMHg), which in some instances accounted for 100% of the mercury present in the sample. Monomethylmercury readily moves through water, and can accumulate in freshwater and marine systems, where it is absorbed and bioaccumulates into the body tissues of fish, shellfish and other wildlife at levels that pose a health risk to humans that consume these toxins.

While Lamborg states that the MMHg levels are much higher than they would be had wastewater not been disposed of into the ground, he does not consider them to be high enough to pose a risk in drinking water. However, considering that monomethylmercury is a neurotoxin that is able to penetrate the skin, and which at high doses can affect muscle and brain tissue that can lead to brain damage or paralysis; combined with its ability to bioaccumulate in the tissue of organisms (including humans), it could potentially pose a severe health risk over time.

“This should make us all think twice about what we dump into the ground. Adding more nitrogen into the ground through wastewater, and even fertilizers for our agricultural fields and golf courses, offers a potential for mercury to accumulate and move through the aquifer to our ponds, lakes, and the ocean. That's something I don't think people are really thinking about,” said Lamborg.

When Lamborg took a closer look at the chemical processes taking place at the second site, he discovered something that intrigued him even.

His observations of the denitrification process – the process whereby the microbes utilize organic carbon and nitrogen to decompose organic matter – revealed high levels of MMHg were occurring as a result of the denitrification process, while previous research has shown low levels of MMHg following decomposition by denitrification.

According to Lamborg: “This kind of thing where you see denitrification resulting in the methylation of mercury has never been observed before.”

Mercury Accumulation

Even more puzzling is the fact that the contaminant plume contains even higher levels of mercury than the original wastewater sources or produced by microbes during the decomposition process. So where does this mercury come from?

“What it looks like is, the mercury that was already there in the aquifer or sand is being mined out when the groundwater goes anoxic,” explains Lamborg. Mercury that has up until now been stored within the ground for thousands of years is being drawn out and is now on the move.

Lamborg notes that this is a community-wide problem at Cape Cod, because the sandy soils characteristic of the area allow wastewater that is disposed into the ground to disappear rapidly through the soil. While it may appear to be 'out of sight and out of mind', toxins like mercury accumulate and reappear in downstream ponds and the ocean.

“This is just one really big example, but it's happening in a small way through everybody's backyard septic system, which leaches a little bit of mercury out of the aquifer and accumulates. You don't need a really big industrial scale thing for this to happen. It's happening everywhere,” Lamborg said.

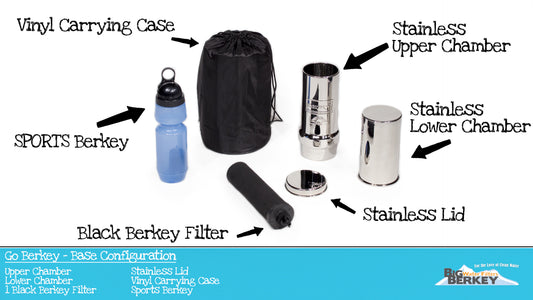

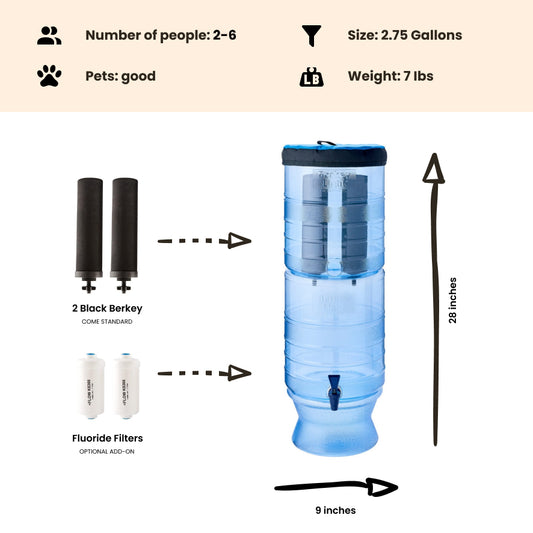

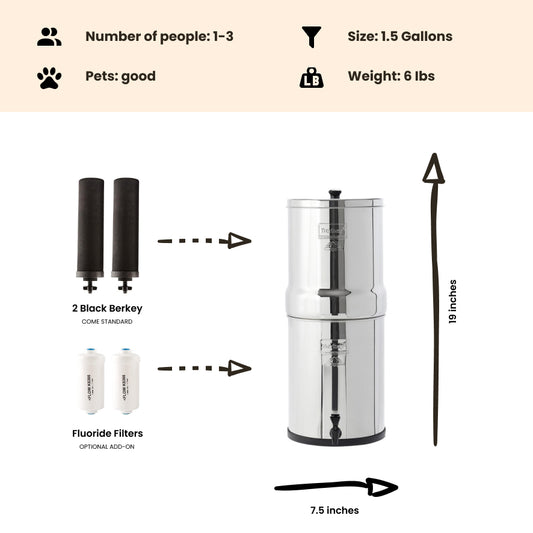

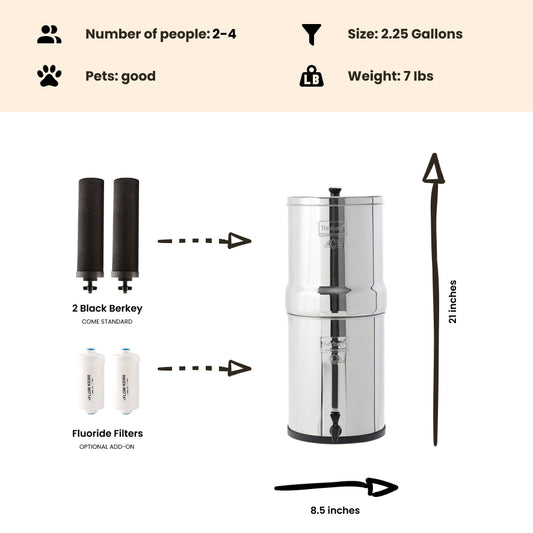

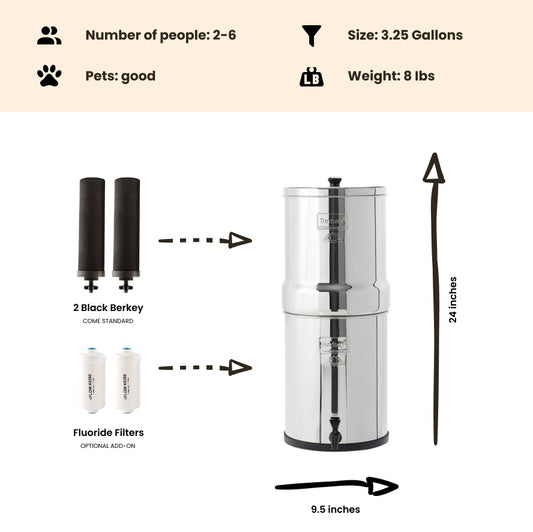

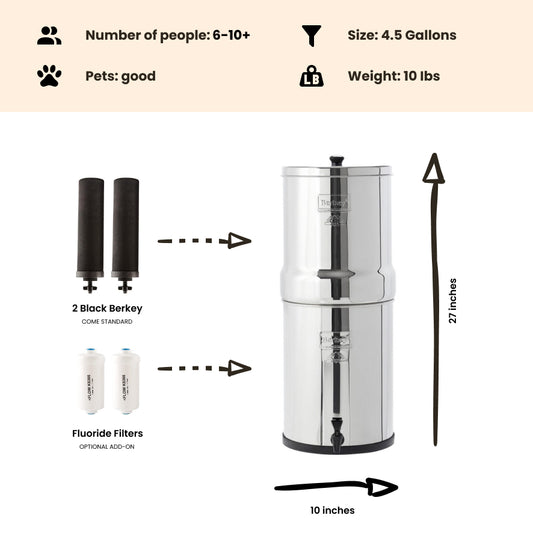

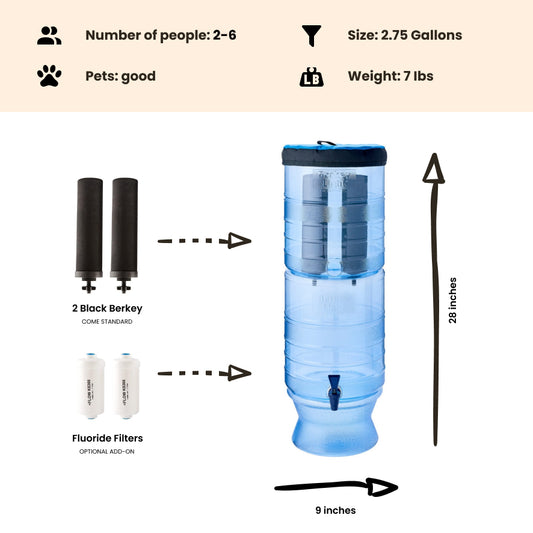

It stands to reason then that if this is happening everywhere, groundwater sources may be contaminated with high levels of mercury. To prevent exposure to this highly toxic contaminant in drinking water, you would be well advised to take precautionary measures to filter out any potential toxins that may be lurking. A Berkey Filter fitted with Black Berkey purification elements can remove a wide range of contaminants commonly found in drinking water, including mercury.

-

Regular price From $302.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

-

Regular price $234.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

-

Sold outRegular price From $305.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

Sold outRegular price From $305.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Regular price $327.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

-

Regular price From $367.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

-

Regular price From $408.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

-

Regular price From $451.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

Dan DeBaun

Dan DeBaun is the owner and operator of Big Berkey Water Filters. Prior to Berkey, Dan was an asset manager for a major telecommunications company. He graduated from Rutgers with an undergraduate degree in industrial engineering, followed by an MBA in finance from Rutgers as well. Dan enjoys biohacking, exercising, meditation, beach life, and spending time with family and friends.

~ The Owner of Big Berkey Water Filters