Toxic Environmental Contaminants Contribute to Antibiotic Resistance

By Dan DeBaunShare

** Antibiotic-resistant bacteria is a growing health problem that has prompted health officials, NGOs and media agencies to increase public awareness of the hazards associated with antibiotic use and misuse.

** Now a University of Georgia ecologist has warned that there may be more to this issue than misuse of antibiotic drugs.

J. Vaun McArthur, an ecologist based at the Odum School of Ecology and the Savannah River Ecology Laboratory, believes that environmental contaminants (primarily heavy metals) could play a role in the rise of bacterial resistance. To test his hypothesis he studied the effects of environmental contaminants in streams surrounding the U.S. Department of Energy's Savannah River Site.

The DoE's Savannah River Site is situated alongside the Savannah River, close to Aiken, South Carolina, and covers an area of 310 square miles. In the 1950s the site was closed to the general public and used to produce materials required for building nuclear weapons. The production of these materials has resulted in toxic waste materials that have contaminated certain areas within the site and impacted streams in the surrounding areas.

McArthur and his fellow researchers collected water and sediment samples from eleven sites along nine streams and proceeded to test five different antibiotics on over 400 strains E. Coli bacteria collected from the streams. Metal contaminants measured at the various sites ranged from low to high.

"The site was constructed and closed to the public before antibiotics were used in medical practices and agriculture," McArthur said. "The streams have not had inputs from wastewater, so we know the observed patterns are from something other than antibiotics."

The results of the study, which were recently published in the journal Environmental Microbiology, found that 8 of the 11 sites tested had high levels of antibiotic resistance. The highest level of antibiotic resistance (in both sediment and water samples) were recorded at the northern-most location on Upper Three Runs Creek, and on two tributaries within the industrial area.

While the Upper Three Runs Creek does flow through agricultural, residential and other industrial areas before entering the Savannah River Site, therefore exposing bacteria in the stream to antibiotics, sites marked U4 and U8 are contained within the site and do not have any known antibiotic input from external sources. There is, however, a long history of contamination from legacy waste at these sites.

McArthur then screened the samples a second time using twenty-three antibiotics on samples collected from U4 and U8, as well as samples collected from a stream nearby that was considered to be free from industrial contaminants.

According to McArthur, more than 95% of bacteria samples collected from these streams showed antibiotic resistance to more than 10 of the 23 antibiotics tested, including antibiotics typically used to treat common bacterial infections such as pink eye, sinus- and urinary infections. The highest levels of antibiotic resistance were recorded at locations U4 and U8 (the streams heavily contaminated with industrial waste).

"These streams have no source of antibiotic input, thus the only explanation for the high level of antibiotic resistance is the environmental contaminants in these streams -- the metals, including cadmium and mercury," McArthur said.

While McArthur acknowledges that wildlife that have been exposed to antibiotics may have contributed by adding waste to these streams, only streams that had a history of industrial waste being discharged into them had bacteria that were resistant to antibiotics — bacteria in the other six streams located in pristine areas within the site that received no industrial input succumbed to antibiotics.

McArthur finds it disconcerting that industrially contaminated water from these antibiotic resistance streams flows into the Savannah River, which flows past residential communities living on the border of South Carolina and Georgia.

According to McArthur: "The findings of this study may very well explain why resistant bacteria are so widely distributed."

Journal Reference

J.V. McArthur et al. Patterns of Multi-Antibiotic-Resistant Escherichia Coli from Streams with No History of Antimicrobial Inputs. Environmental Microbiology, (Nov 2015); doi:10. 1007/ s00248-015-0678-4

-

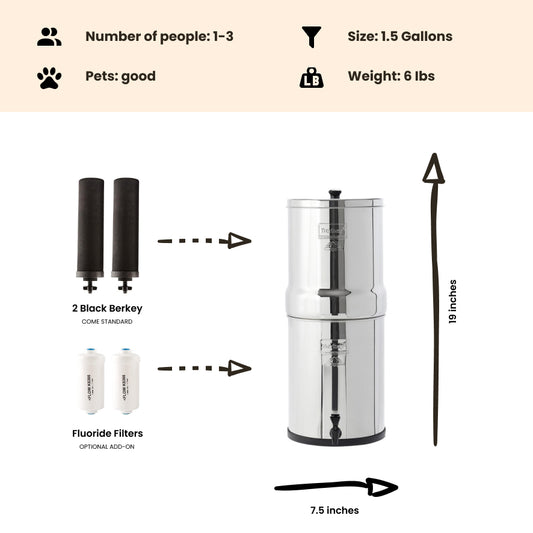

Regular price $234.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

-

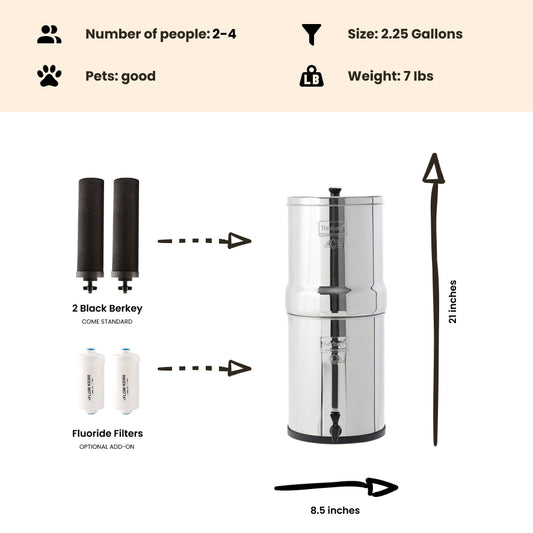

Regular price $327.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

-

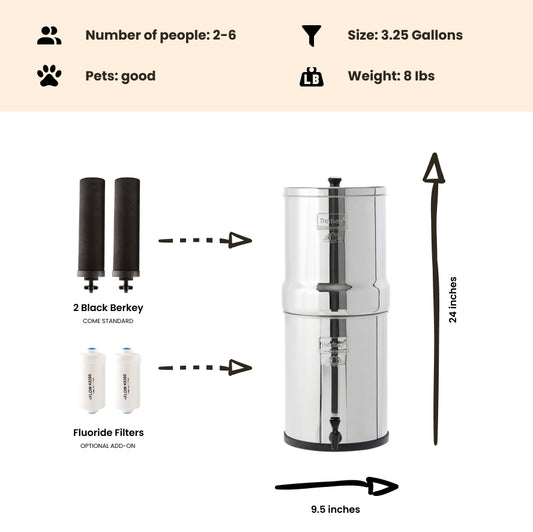

Regular price From $367.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

-

Regular price From $408.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

-

Regular price From $451.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

-

Regular price From $478.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

-

Regular price $332.50 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

$350.00 USDSale price $332.50 USDSale

Dan DeBaun is the owner and operator of Big Berkey Water Filters. Prior to Berkey, Dan was an asset manager for a major telecommunications company. He graduated from Rutgers with an undergraduate degree in industrial engineering, followed by an MBA in finance from Rutgers as well. Dan enjoys biohacking, exercising, meditation, beach life, and spending time with family and friends.

~ The Owner of Big Berkey Water Filters