A Third of the World's Major Groundwater Basins are in Distress

By Dan DeBaunShare

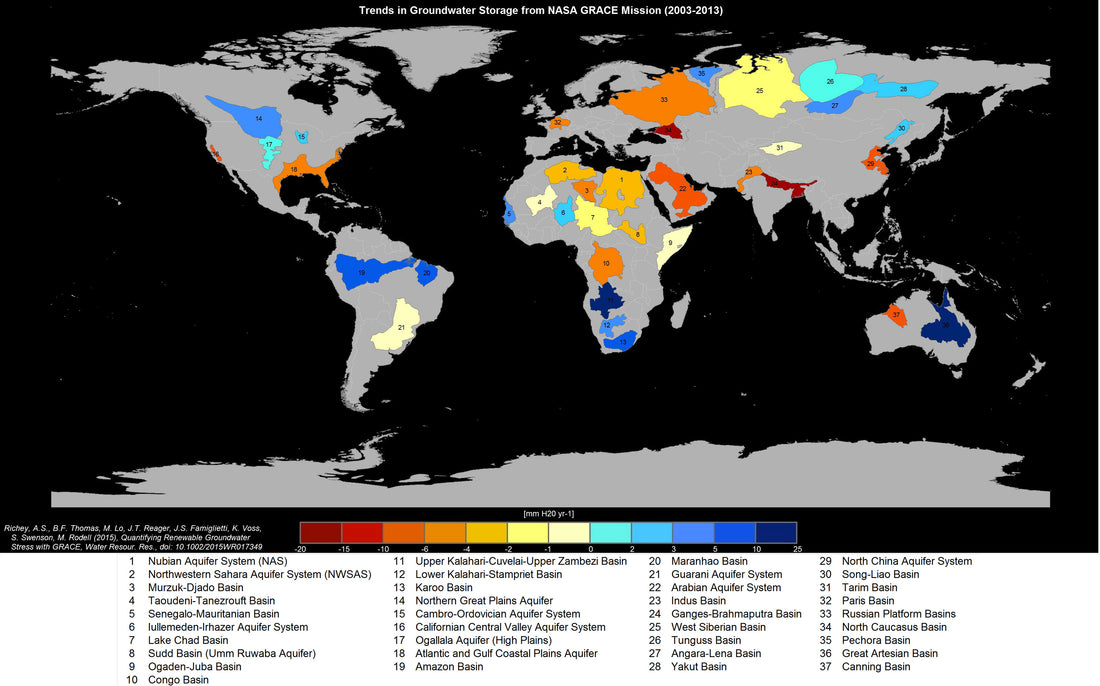

Two new research studies conducted by a research team comprised of scientists from the University of California, Irvine; UC Santa Barbara; National Taiwan University; and NASA, the National Center for Atmospheric Research, who assessed data supplied by NASA's Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) satellites, have found that a third of the world's major groundwater reserves are rapidly becoming depleted due to human demands, despite there being little information regarding how much water they still contain.

According to the reports, which were recently published in Water Resources Research, this means that a significant portion of the global human population is consuming groundwater at a rapid pace without any knowledge of when these groundwater supplies may run dry.

"Available physical and chemical measurements are simply insufficient," said principal investigator Jay Famiglietti, who is a professor at UCI and also the senior water scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. "Given how quickly we are consuming the world’s groundwater reserves, we need a coordinated global effort to determine how much is left."

In the initial report, the scientists show that 13 out of 37 of the world's major aquifers assessed over a 10 year period between 2003-2013, were having water extracted at unsustainable levels due to their receiving little or no replenishment.

Of these, 8 were considered to be "overstressed," as they were not being replenished as the water was drawn off for use, while 5 were considered "extremely" or "highly" stressed, according to the degree of replenishment -- although these aquifers were being rapidly depleted, they were being replenished, but at a much slower rate than what water was being used.

The researchers found that the most overstressed groundwater basins were situated in the driest areas of the world, where populations were forced to draw heavily from groundwater reserves. It is anticipated that population growth together with climate change will exacerbate the problem in the future.

"What happens when a highly stressed aquifer is located in a region with socioeconomic or political tensions that can’t supplement declining water supplies fast enough?" asked Alexandra Richey, lead author of both studies. "We’re trying to raise red flags now to pinpoint where active management today could protect future lives and livelihoods."

The researchers determined that the world's most overstressed groundwater basin is the Arabian Aquifer System -- a source of water for over 60 million people, followed by the Indus Basin siutated in Pakistan and India, with North Africa's Murzuk-DjadoBasin the third most stressed. While the Californian Central Valley basin is heavily used by the agricultural sector and thus rapidly becoming depleted, it fared slightly better but was still considered highly stressed by the authors of the first study.

"As we’re seeing in California right now, we rely much more heavily on groundwater during drought," explains Famiglietti. "When examining the sustainability of a region’s water resources, we absolutely must account for that dependence."

In the second companion paper that was also published in Water Resouces Research, the researchers concede that estimates of the total volume of the world's groundwater vary greatly and are vague at best, leaving them to conclude that little is known about how much usable groundwater actually remains in the world, but this is likely to be much less than these outdated estimates.

When the researchers compared the groundwater loss rates derived from the satellite data to the limited data on groundwater availability, they discovered major discrepancies when projecting "time to depletion". For example, in the Northwest Sahara Aquifer System -- an overstressed groundwater basin -- estimated time to depletion varied between 10 - 21,000 years.

"We don’t actually know how much is stored in each of these aquifers. Estimates of remaining storage might vary from decades to millennia," said Richey. "In a water-scarce society, we can no longer tolerate this level of uncertainty, especially since groundwater is disappearing so rapidly."

The study also points out that groundwater depletion is already showing signs of ecological impacts, including changes in river flow rates, reduced water quality, and land subsidence.

Underground aquifers tend to be found in sediments or rock located deep beneath the surface of the Earth, making it difficult and expensive to drill into the bedrock to determine where the water bottoms out. But according to the authors, this is necessary and is a task that has to be undertaken if we wish to gain a better understanding of the volume of groundwater remaining on our Planet.

Journal References:

Richey, A. S., Thomas, B. F., Lo, M.-H., Reager, J. T., Famiglietti, J. S., Voss, K., Swenson, S. and Rodell, M. (2015), Quantifying renewable groundwater stress with GRACE. Water Resour. Res.. Accepted Author Manuscript. doi:10.1002/2015WR017349

Richey, A. S., Thomas, B. F., Lo, M.-H., Famiglietti, J. S., Swenson, S. and Rodell, M. (2015), Uncertainty in global groundwater storage estimates in a total groundwater stress framework. Water Resour. Res.. Accepted Author Manuscript. doi:10.1002/2015WR017351

-

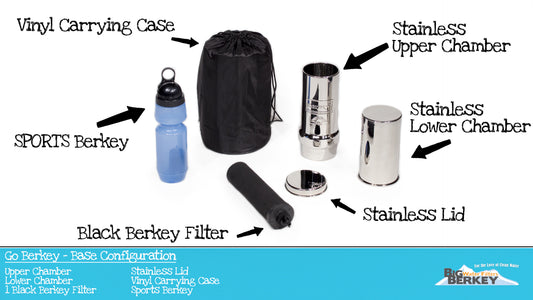

Regular price $234.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

-

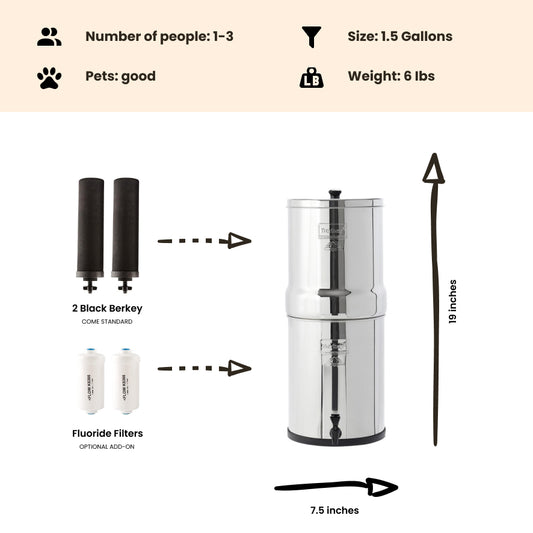

Regular price $327.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

-

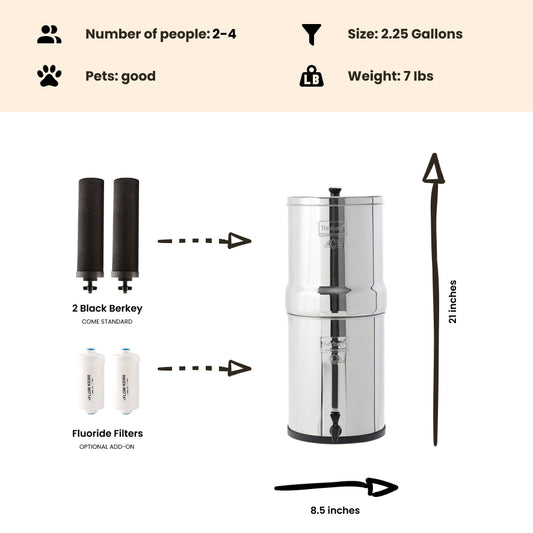

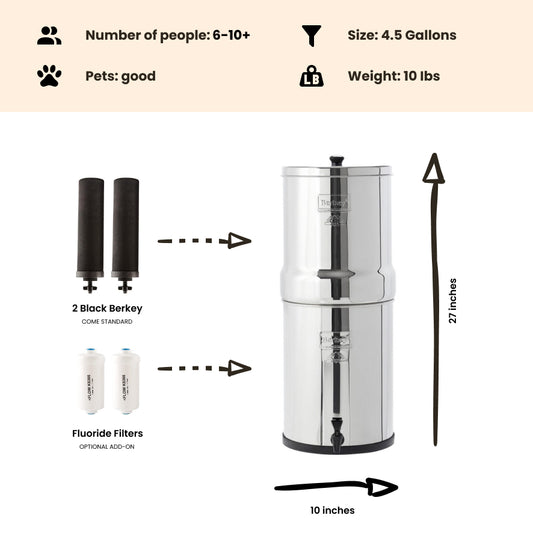

Regular price From $367.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

-

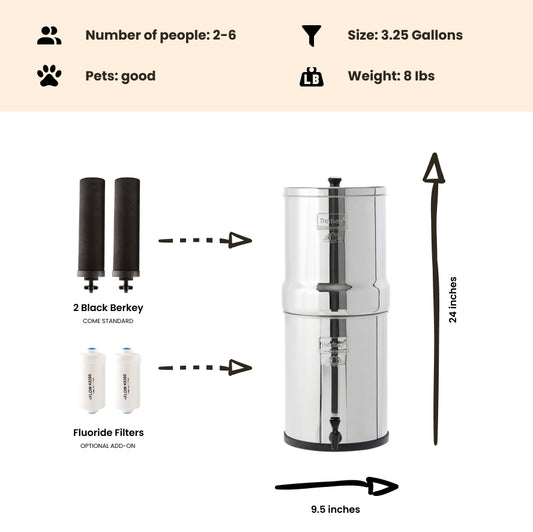

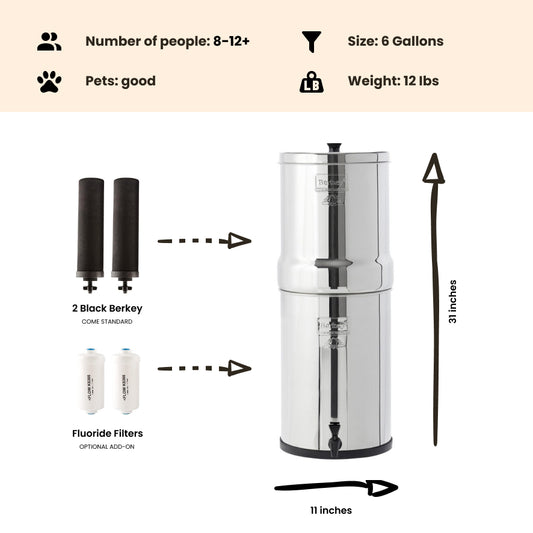

Regular price From $408.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

-

Regular price From $451.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

-

Regular price From $478.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

-

Regular price $332.50 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

$350.00 USDSale price $332.50 USDSale

Dan DeBaun is the owner and operator of Big Berkey Water Filters. Prior to Berkey, Dan was an asset manager for a major telecommunications company. He graduated from Rutgers with an undergraduate degree in industrial engineering, followed by an MBA in finance from Rutgers as well. Dan enjoys biohacking, exercising, meditation, beach life, and spending time with family and friends.

~ The Owner of Big Berkey Water Filters